The art works were produced for Castro’s Organisation of Solidarity of the People of Asia, Africa and Latin America (Ospaaal), which was born out of the Tricontinental Conference, hosted in Havana in 1966, to combat US imperialism.

“A lot of African countries were represented as part of the delegation there, including liberation movements. And Castro connected with a few leaders, particularly Amílcar Cabral from Guinea-Bissau,” Olivia Ahmad, the curator of the exhibition at the House of Illustration, told the BBC.

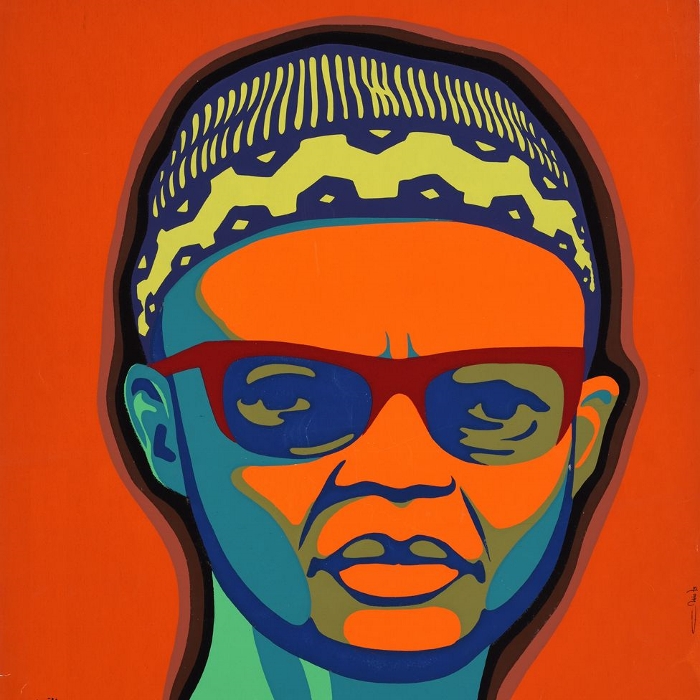

Amílcar Cabral on the poster Day of solidarity with people of Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde Islands, 1974

Olivio Martínez Viera

courtesy of The House of Illustration in London. Copyright: Ospaaal, The Mike Stanfield Collection // BBC NewsCabral led the fight against Portuguese colonial rule in Guinea-Bissau and the Cape Verde islands, but was assassinated in 1973, a year before Guinea-Bissau became independent.

Ms Ahmad says more Tricontinental Conferences were planned, but never happened so Ospaaal’s publishing arm became an important way to keep in contact and share information – and posters were folded up and put inside its publications.

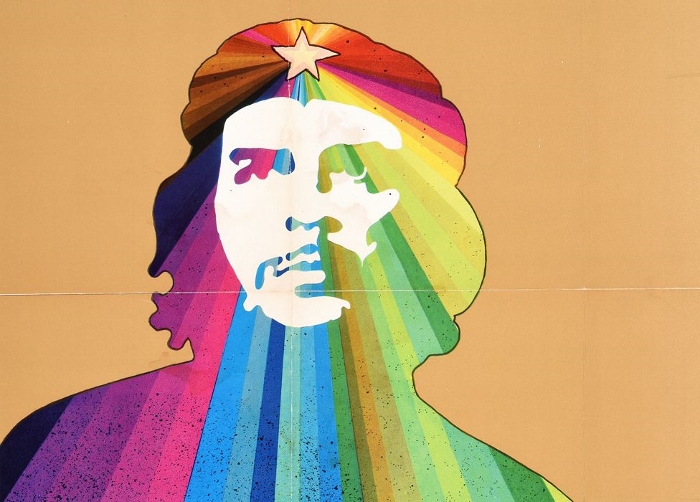

Latin America’s most recognisable revolutionary, Ernesto “Che” Guevara, was “probably the most depicted across the whole output of Ospaaal”, she says.

“But there are recurring ones of these African leaders being celebrated in the same way and commemorated as well.”

Che Guevara depicted in a poster from 1969

Alfredo G Rostgaard

courtesy of The House of Illustration in London. Copyright: Ospaaal, The Mike Stanfield Collection // BBC NewsGuevara infamously went to what is now Democratic Republic of Congo in 1965 on a failed mission to foment revolt against the pro-Western regime four years after the assassination of Congolese independence hero Patrice Lumumba.

Lumumba’s killing, four months after he had being elected the country’s first democratic prime minister, was widely blamed on US and UK intelligence agencies.

Patrice Lumumba featured on the poster Day of Solidarity with the Congo, 1972

Alfredo G Rostgaard

courtesy of The House of Illustration in London. Copyright: Ospaaal, The Mike Stanfield Collection // BBC News”The portraits are particularly interesting because they have all these pop art influences that you might not expect to see, so they are kind of celebrating people but in a genuinely celebratory way – rather than having a sort of like lumpen socialist-realist aesthetic,” says Ms Ahmad.

The works showcased in Designed in Cuba: Cold War Graphics exhibition were produced by 33 designers, many of them women – who made some of those most enduring images.

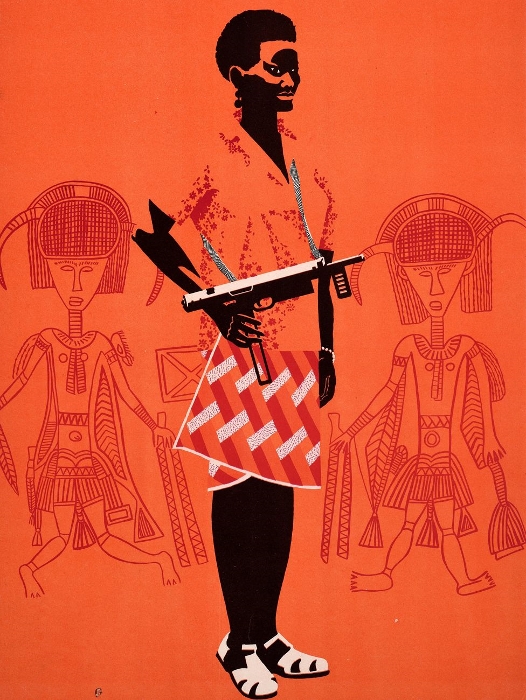

A poster about Guinea-Bissau showing a woman holding a machine gun is by Berta Abelenda Fernandez, “one of the women who made some of the most iconic designs for Ospaaal”, says Ms Ahmad.

Day of Solidarity with the People of Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde, 1968

Berta Abelénda Fernández

courtesy of The House of Illustration in London. Copyright: Ospaaal, The Mike Stanfield Collection // BBC NewsIt is one of the recurring motifs – women with guns – showing them taking an active role and the Tricontinental magazine had “quite a lot of contributions from women and articles about women as well on guerrilla fronts”, Ms Ahmad says.

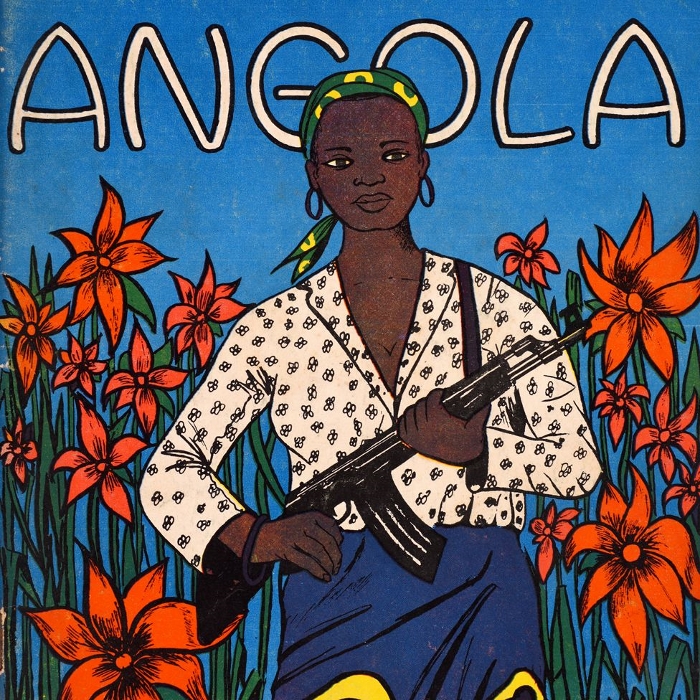

A cover of the Tricontinental magazine in 1995

OSPAAAL

courtesy of The House of Illustration in London. Copyright: Ospaaal, The Mike Stanfield Collection // BBC NewsCastro played a major role in Angola, unlike Cuba’s secret operations in Africa in the 1960s, where he saw an opportunity to exert his brand of international solidarity to make a difference on a global scale.

Ahead of Angola’s independence from Portugal in 1975, Castro sent elite special forces and 35,000 soldiers to support the Marxist MPLA movement to stop apartheid South African troops installing pro-US movements to power.

Day of Solidarity with Angola, 1972

José Lucio Martínez Pedro

courtesy of The House of Illustration in London. Copyright: Ospaaal, The Mike Stanfield Collection // BBC NewsAccording to Alex Vines of the think tank Chatham House, at least 4,300 Cubans are thought to have died in conflicts in Africa, half of them in Angola alone where the civil war did not end until 2002.

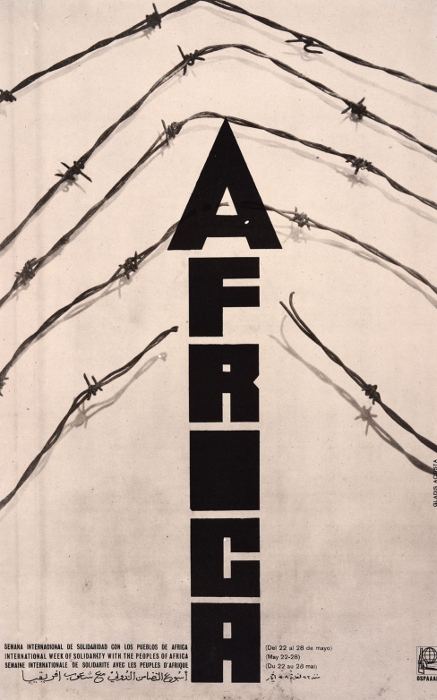

The posters carrying messages of solidarity to liberation fighters usually did so “using bold visual metaphors or quite simple visual propositions”, says Ms Ahmad.

They tended to have captions at the bottom, usually in four languages – English, Spanish, French and Arabic – “to help them be more universal because they were intended for circulation rather than to be seen in Cuba”, she says.

International Week of Solidarity with the Peoples of Africa, 1970

Gladys Acosta Ávila

courtesy of The House of Illustration in London. Copyright: Ospaaal, The Mike Stanfield Collection // BBC NewsOspaaal oversaw a huge publishing operation, which involved a lot of paper and ink. Olivio Martínez Viera, a designer who was at Ospaaal from almost the beginning, said there were often material shortages that meant they had to be quite creative.

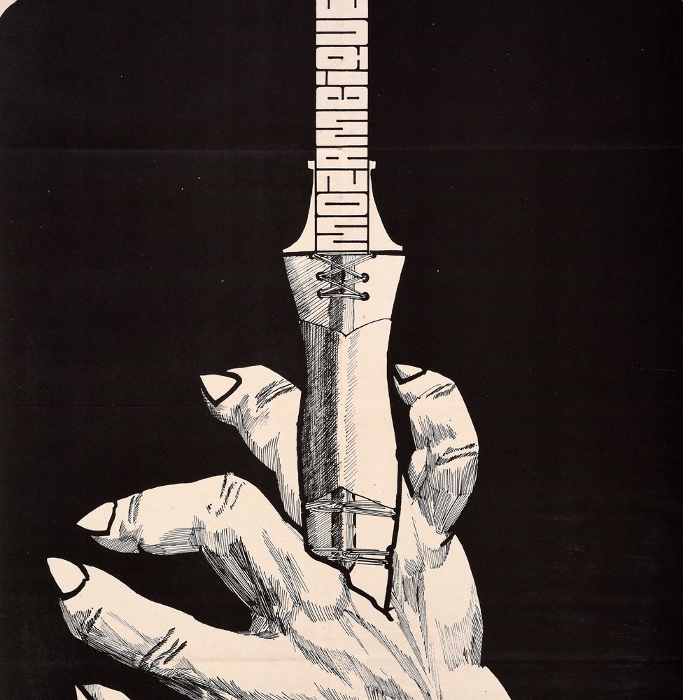

Day of World Solidarity with the Struggle of the People of Mozambique, 1973

Olivio Martínez Viera

courtesy of The House of Illustration in London. Copyright: Ospaaal, The Mike Stanfield Collection // BBC NewsViera “talks really fondly about that time, about Ospaaal being a real nurturing space for experimentation and having the freedom to create these really direct visual metaphors like the Mozambique” design of a dagger plunging through a hand, says Ms Ahmad.

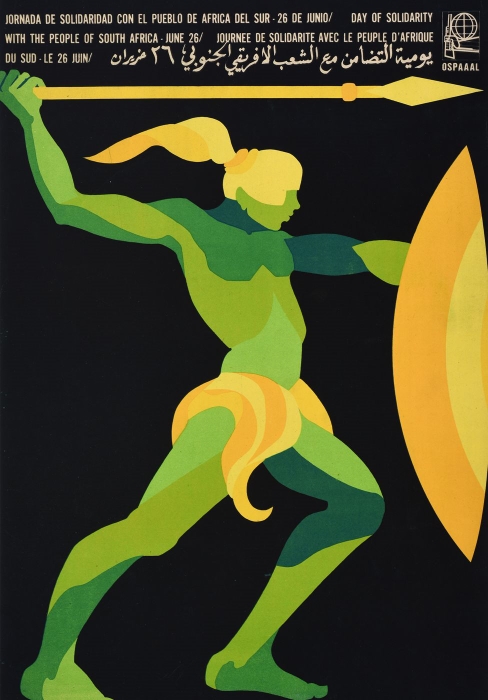

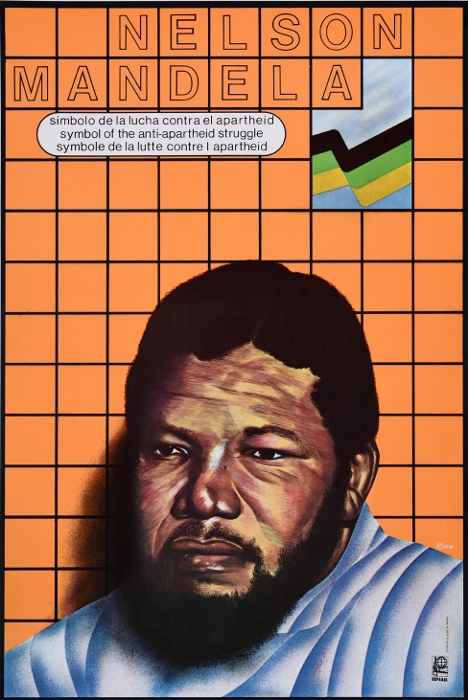

Much of Ospaaal’s output was directed towards the fight against white-minority rule in South Africa, which did not end until 1994 when anti-apartheid leader Nelson Mandela was elected president.

Day of Solidarity with the People of South Africa, 1968

Berta Abelénda Fernández

courtesy of The House of Illustration in London. Copyright: Ospaaal, The Mike Stanfield Collection // BBC NewsTeishan Latner’s book Cuba Revolution in America shows a satirical advert for South African Airways included in Tricontinental’s July-August 1968 issue promising “an unforgettable vacation in the land of APARTHEID, where Africans are massacred, where prisons overflow with patriots fighting against white racists, where thousands of Blacks work as slaves in the gold mines, where miles and miles of land are used for concentration camps”.

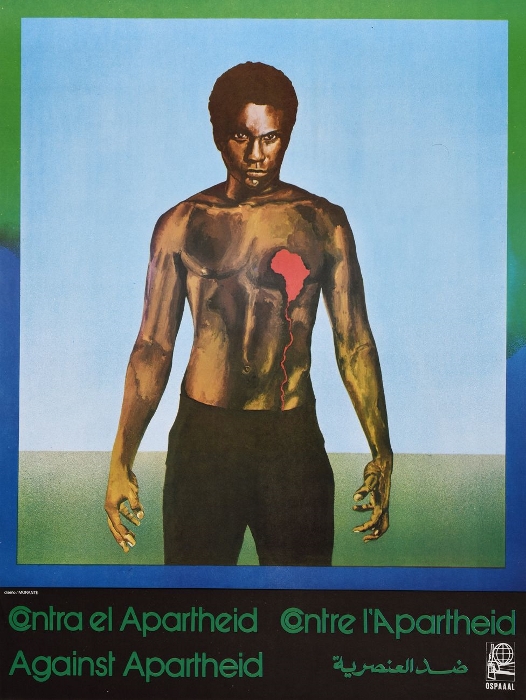

The images on the Ospaaal posters were just as blunt:

South Africa – Against Apartheid, 1982

Rafael Morante Boyerizo

courtesy of The House of Illustration in London. Copyright: Ospaaal, The Mike Stanfield Collection // BBC NewsAfter Mandela was imprisoned by the apartheid authorities in 1964, it was illegal to photograph or republish a photo of him in South Africa. This poster came out in 1989, a year before his release after 27 years in jail.

Nelson Mandela, 1989

Alberto Blanco González

courtesy of The House of Illustration in London. Copyright: Ospaaal, The Mike Stanfield Collection // BBC NewsThe artists producing the posters were mainly based in Havana and were trying to understand the political context for real people often using press photographs, says Ms Ahmad.

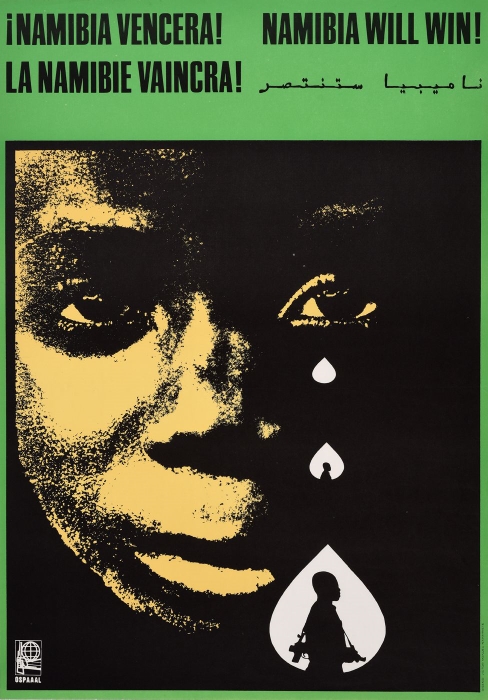

Namibia Will Win! 1977

Víctor Manuel Navarrete

courtesy of The House of Illustration in London. Copyright: Ospaaal, The Mike Stanfield Collection // BBC News”They are very graphically interesting… trying to sympathise with all these geopolitical messages. I think most are hits and then some of them are slightly questionable.”

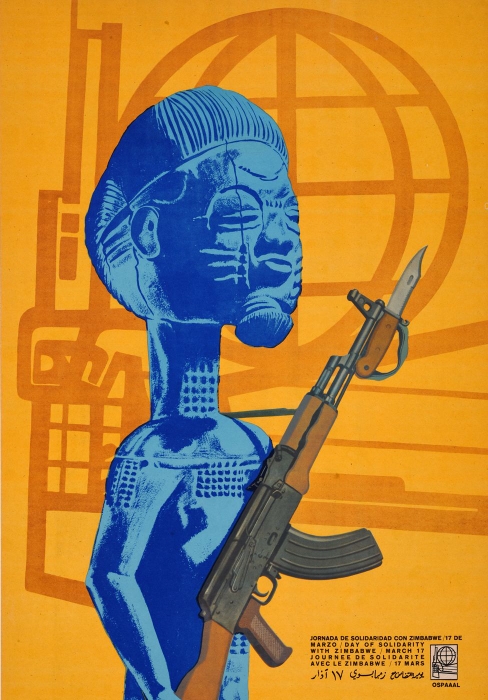

It is not always clear what some of the stylised sculptures were based on. “I think they’re basically just trying to relate contemporary struggle in a long history,” says Ms Ahmad.

Day of Solidarity with Zimbabwe, 1969

Jesús Forjans Boade

courtesy of The House of Illustration in London. Copyright: Ospaaal, The Mike Stanfield Collection // BBC NewsOspaaal closed this year saying its work was done.

“I think the context for those international movements has really changed, so you can see why,” says Ms Ahmad.

But the curator says Ospaaal’s work and diversity of output has been impressive and its ability to sum up complex messages in an engaging way.

“Also it’s interesting to see what is essentially propaganda executed with humour and often levity,” she says.

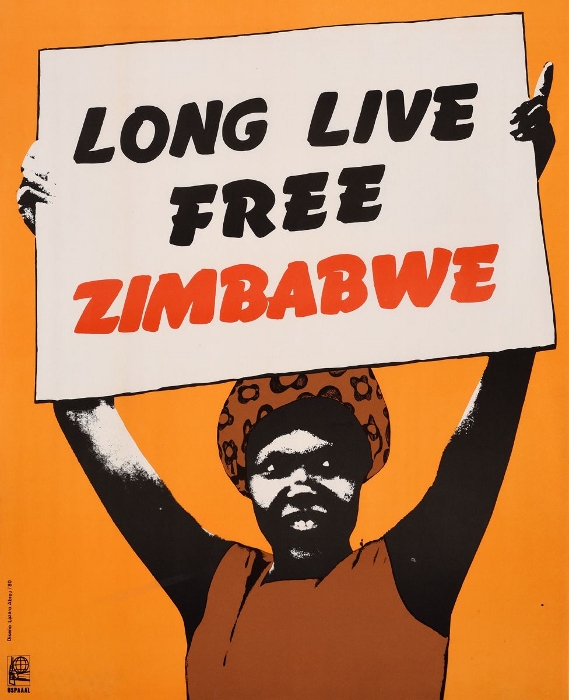

Long Live Free Zimbabwe, 1980

Lázaro Abreu Padrón

courtesy of The House of Illustration in London. Copyright: Ospaaal, The Mike Stanfield Collection // BBC NewsImages courtesy of The House of Illustration in London. Copyright: Ospaaal, The Mike Stanfield Collection